I. Preamble

One day, Takeshi receives a letter informing him that he needs to return to hospital because of some worrying test results. He’s 60 years old and terrified of dying. His wife assures him that it’s nothing; he’s probably fine. Takeshi isn’t convinced. He hunkers over himself in the hospital waiting room. He doesn’t want to die.

Later that evening, Takeshi sits at the counter of an izakaya. This informal Japanese bar sells tall glasses of beer and cheap plates of hearty food. He’s watching the woman behind the counter ladle a stewed tofu dish known as kasane into a bowl. The results had come back negative. Takeshi is fine and he’s determined to celebrate!

The hostess places the hot bowl of stew in front of him.

“I know that it’s bad for my health but that’s what makes it taste so good!” He thinks as he surveys the dish adoringly, “An onion topping - what a great idea!”

Takeshi Kasumi is the main character of Samurai Gourmet, a short Japanese web series about a man discovering joy amidst a devastating absence of purpose. Takeshi has recently retired from a career in nebulous bureaucracy, what David Graeber concisely referred to as a bullshit job - a daily grind with no purpose, no meaning, an awful dream. Conversely, his retirement is portrayed as a rebirth. A continuation of a life that preceded employment. In the first episode Takeshi finds himself at a loose end and so he wanders the streets. Eventually he stumbles upon a cafe, orders food, and it changes his life.

Takeshi’s job, with its absolute domination of his life, prevented him from experiencing food in a way that gave him joy. Now unburdened by work, this joy is a revelation to him. This is why he’s alive: To taste and to enjoy food. To revel in the exquisite moments of pleasure created by it. Eat up!

The reason that I’m bringing attention to this Japanese hedonist is because he provides a useful counterpoint to the pernicious relationship Britain has with food. It’s a relationship bound up with British culture, class structure, and capitalism. It reaches deep into our psyche and reveals the wretched state we’ve got ourselves into.

II. Pleasure Map

You’re holding an orange. It’s so spectacular that we stole its name - when we describe the orange clouds swirling through the skies of Jupiter we are identifying that they are some variation of the hue of the fruit resting in your hand. An indelible mark is made upon the cosmic by the substance of the earth.

You pass your hand across its skin. It feels like polished leather and as you scratch it you can smell the oils held inside. You take a deep breath and your nostrils are filled with a citrus perfume. The smell unlocks deep memories. Your mind crackles with images.

You dig your nails into the rind and pull the fruit apart. As the skin bursts aromatic oils saturate the air. Juice drips from the bright flesh within. You bring the fruit to your mouth…

The experience of food begins long before the first bite but it does culminate in taste, which owes its existence to the gustatory system. This system is composed of various taste receptors in the mouth and nose which are all bound together within a part of the brain called the gustatory cortex. It’s believed that taste initially existed as a prudent hedonic compass, providing moments of pleasure when our ancestors ate something beneficial counterposed by moments of disgust when they ate something harmful1. We have long left that simple compass behind. Now the pleasure of eating food, our hedonic reaction, is more complex and difficult to quantify but we can divide it into the classic duality 2: Objective and subjective hedonic reactions. Objective hedonic reactions to food owe themselves to its content, plus the corresponding tastes, which ignite neurons and begin a neural reaction that may or may not be conscious. The result is an undeniable and somewhat mechanical feeling of pleasure. Junk food leans heavily on this form of hedonic reaction. Subjective hedonic reactions are vastly more complex, relying on the framing of a situation. An example: The warmth and serenity of eating a meal with loved ones. The context of that experience shifts our perspective and enhances the pleasure we experience. This is the joy we seek to imbue our lives with.

When Takeshi excitedly digs into his bowl of kasane, he’s experiencing both forms of hedonic reaction. The stew is rich, full of fat and flavour, the simple hedonic reaction provided by its material ingredients. This is then compounded by the situation; his relief following the news of his good health and the social relationship with the hostess, the worker, who he witnesses make the food. The unification and subsequent magnification of these pleasures is at the heart of Takeshi’s path to joy. Eating food is an opportunity to reflect and revel in the experience of being alive. Taste, like all other senses, is a fundamental component of how we engage with the world around us and it should be embraced unashamedly.

III. Numbers

A slice of cheesecake held above a naked flame burns intensely. The fire joyously consumes those two towering columns of taste; fats and sugars. We observe a transformation, or rather a reduction, from glucose to ash which yields energy and heat. This process is a crude replication of the metabolic pathways within the human body that convert material substance into immaterial lifeforce. Through this lens food is fuel. The energy generated by that fuel, when consumed by the fire, is measured in units of calories. This primitive measurement of things has since been attributed to our meals, thereby acquiring vastly more social significance than it ever deserved.

In Europe calories first significantly intruded into public life in 1990 through changes in food labelling. These were based on the requirements of the EU Nutrition Labelling Directive3 which justified their policy change with the following:

“There is growing public interest in the relationship between diet and health and in the choice of an appropriate diet to suit individual needs […] knowledge of the basic principles of nutrition and appropriate nutrition labelling of foodstuffs would contribute significantly towards enabling the consumer to make this choice”

Here food is being framed from the implicit perspective of consumption (the consumer) rather than the perspective of production (the producer). Food is being defined by the choice made prior to the point of sale and it is this choice that rules the market. The discussion of how food labelling has an effect on consumer choice is an articulation of the perceived use value of food that goes into this decision. Use value is the subjective value of the foodstuff to the consumer, how it satisfies desires and needs. This is food as a commodity where the human labour that has gone into its production is disjointed from the monetary value of the product. In many ways we now act as if food were simply teleported onto our supermarket shelves from some unknown place. This abstraction, shedding the human reality of the production process, is a necessary first step in the total dehumanisation that is to come.

The relationship between ourselves and the commodities we buy is generally treated as a one way mechanism by politicians and the policies they set out: We, the public, are framed as consumers and the commodity is subjected to the consumer. The deceit here is inherent as these policies are instruments of social control. This control is successful as the public, through consumers, are conversely subjected to the commodity. Simply put, how a society defines and regulates products purposefully returns to define and regulate that society. This tautological structure, a feedback loop, is unavoidable. Under capitalism this naturally results in the contortion of the individual in relation to the world around them.

In a vacuum, nutritional information on food labelling is good. We obviously need to know what we’re putting into our bodies. Things become complicated when this information is framed and then approached with intentions that are not our own. The most obvious example of this is the diet industry which is entirely parasitic. In order to convince someone to employ a diet plan they must first believe that there’s something wrong with them. It’s submission “to a rule that says you are worth nothing more than the number on your scale”4. Diet plans may differ but they all share that same bottom line: Alienation. This is not unique to the diet industry. It is a process built into capitalism in which the commodity is an agent of dehumanisation.

IV. Holograms

We dream of passing through ourselves and finding ourselves in the beyond: The day when your holographic double will be there in space, eventually moving and talking, you will have realised this miracle. Of course, it will no longer be a dream, so its charm will be lost.

The TV studio transforms you into holographic characters: One has the impression of being materialized in space by the light of projectors, like translucid characters who pass through the masses exactly as your real hand passes through the unreal hologram without encountering any resistance - but not without consequences: having passed through the hologram has rendered your hand unreal as well.

Baudrillard’s hologram is a description of our annihilation and reflection by the (increasingly antiquated) spectacle of television. Like a parade through a funhouse, we see our contorted reflections in its characters. Just as a continent is replicated by a map, a person is replicated by a hologram. This trick; the translation of human to image comes at a price: There is no majesty in the mountains of a map. Holograms aren’t generated only by television. Capitalism, through commodification, populates our world with holograms…

‘I woke up one morning, to find that the benign light of technology had projected a hologram into my life. It lingers in the corner of the room, I think.

It hasn’t spoken yet but I know what it wants to say - my desires culminate in its abstract form. Its motionless shape carves the words into my mind.'

I am what you could be.

‘And now I don’t understand what I am, but know what I’m not.'

Thanks to capitalism’s obsession with the commodity, where the world becomes a collection of values, calories are a conceptual flash point. They’re a simple mathematical problem to overcome, something to be subtracted from something else. The consumer enters into this equation and, just like food, is abstracted. What began as a human is measured, quantified, and understood until it’s a thing, a dataset. This is the ultimate fate of the consumer, to be consumed by the commodity and then regurgitated as a thing over and over again. The hologram arrives. The moment this occurs both the human being and the food they eat begin to orbit each other like a binary star system, each a pattern of sacred numbers and each responding to the other.

Having been convinced of their own inadequacy, the regurgitated consumer-thing is cursed to forever seek the solution to themselves through the commodity, chasing their hologram. As their humanity is contorted, they lose sight of their reflection in the world around them. It increasingly becomes foreign and strange. This particular form of alienation is known as reification. Unfortunately, the foundational issue in this instance - the inadequacy - was a fabrication and done to sell products. There can be no conclusive end to this torture, alienation is an integral part of the system; it convinces people to buy products, which generates more profit, and perpetuates the industry.

Guy Debord’s Society of The Spectacle comprehensively outlines this process in the context of his spectacle6:

In the spectacle’s basic practice of incorporating itself into all the fluid aspects of human activity so as to possess them in a congealed form, and of inverting living values into purely abstract values, we recognise our old enemy the commodity, which seems at first glance so trivial and obvious, yet which is actually so complex and full of metaphysical subtleties. […]

The world at once present and absent that the spectacle holds up to view is the world of the commodity dominating all living experience. The world of the commodity is thus shown for what it is, because its development is identical to people’s estrangement from each other and from everything they produce.

We are not things. We are not holograms. We are people. The numbers assigned to the world around us do not define us. In the hands of businesses, corporations, and capital they are a wild compass desperately pointing towards the pole of some alien planet, invisible and lifeless. Believing this is easier said than done. Especially when states are willing to abuse alienation for social control.

V. 2021 Britain

I saw also the dreadful fate of Tantalus, who stood in a lake that reached his chin; he was dying to quench his thirst, but could never reach the water, for whenever the poor creature stooped to drink, it dried up and vanished, so that there was nothing but dry ground - parched by the spite of heaven. There were tall trees, moreover, that shed their fruit over his head - pears, pomegranates, apples, sweet figs and juicy olives, but whenever the poor creature stretched out his hand to take some, the wind tossed the branches back again to the clouds.

As of 2021, the “choice” of food is about to become inescapable. Government legislation will force restaurants and cafes to pair every meal with its calorific value. The announcement of this policy was accompanied by the following text7:

“It is estimated that overweight and obesity related conditions across the UK cost the NHS £6.1 billion each year. Almost two-thirds (63%) of adults in England are overweight or living with obesity – and 1 in 3 children leave primary school overweight or obese.”

This is immediately followed by a quote from Public Health Minister Jo Churchill: “Our aim is to make it as easy as possible for people to make healthier food choices for themselves and their families, both in restaurants and at home.”

Here, food becomes an active part of the British government’s solution to obesity which has been framed as an economic problem. Economic problems are useful as they can be extracted from their social context and treated with the raw callousness of the Conservative party’s ideology. No longer are there people; only burdens, and it is the responsibility of a society to remove these burdens. This is the logic of the Conservative Party of Great Britain. A political party unmatched in how utterly enfeebled it has made the populace over which it rules by developing and exploiting the nation’s collective neurosis. In two successive sentences in the Government’s statement we are told that obesity is an economic burden which the British public are paying for (through the publicly funded NHS) and then that the majority of the British public are themselves obese. The obvious response to this is: Who cares? What if the nation wants to be fat? And how is antagonising people an effective way of raising genuine concerns (if there are any)?

One thing is certainly true; everyone deserves the encouragement and opportunity to be as healthy as they possibly can be. A healthy diet is a key part of that and educating people as to what such a diet would consist of can only be good. The Public Health Minister likewise insists this. However, calories are merely a footnote here. If we’re primarily concerned with the energy content in a diet then we shouldn’t consider calories but caloric availability. Caloric availability describes how accessible a foodstuff’s calories are and therefore how easily it is digested. A simple example is sweetcorn: Sweetcorn can be used to make tortillas when it is ground into a flour and therefore has the same number of calories as the tortilla it produces. Because it is unprocessed, sweetcorn is more difficult to digest so it passes through our bodies without the total energy content being extracted and has a lower caloric availability8,9. In short, the sacred number around which we are increasingly contorting ourselves is the useless measure of a broken framework.

Why choose this path? Initially, capitalism sent us barrelling into a world densely packed with foods high in sugars and fats. Processed food is easy to produce and easy to sell. Over the recent decades productivity has increased without a compensating wage increase. Physically or mentally people were (and still are) returning home more and more exhausted each day. Why expend energy cooking when you’re tired? Why not grab something quick and easy (and full of sugar and fat) that can give you the explosive hedonic reaction you need? Decades later, the state is attempting to reverse course without rejecting the system that got us here.

The solution we are seeing play out in our supermarkets is a mimicry of the past. Shelves are filled with foods that have been designed and refined in a laboratory to contain less sugar, fat, X, Y and Z. These products are recreations that provide the same objective hedonic reaction without the “chemical cost” upon which their predecessors relied. Driven by government policy, we are witnessing the alienated consumer returning to the commodity and imposing themselves upon it. A complete circuit of the feedback loop. The end point is the commodity becoming a simulation of what it once was (which is itself an abstraction). The ideal diet here is composed of foods that occupy no material reality but, like a phantom, delight the senses and the senses alone. If the commodity is once again to return and transform us one can only conclude that we too shall eventually be turned into ghosts as we continually reach for something that forever escapes us.

To avoid this fate, we must ask ourselves where is the joy?

VI. Reclamation

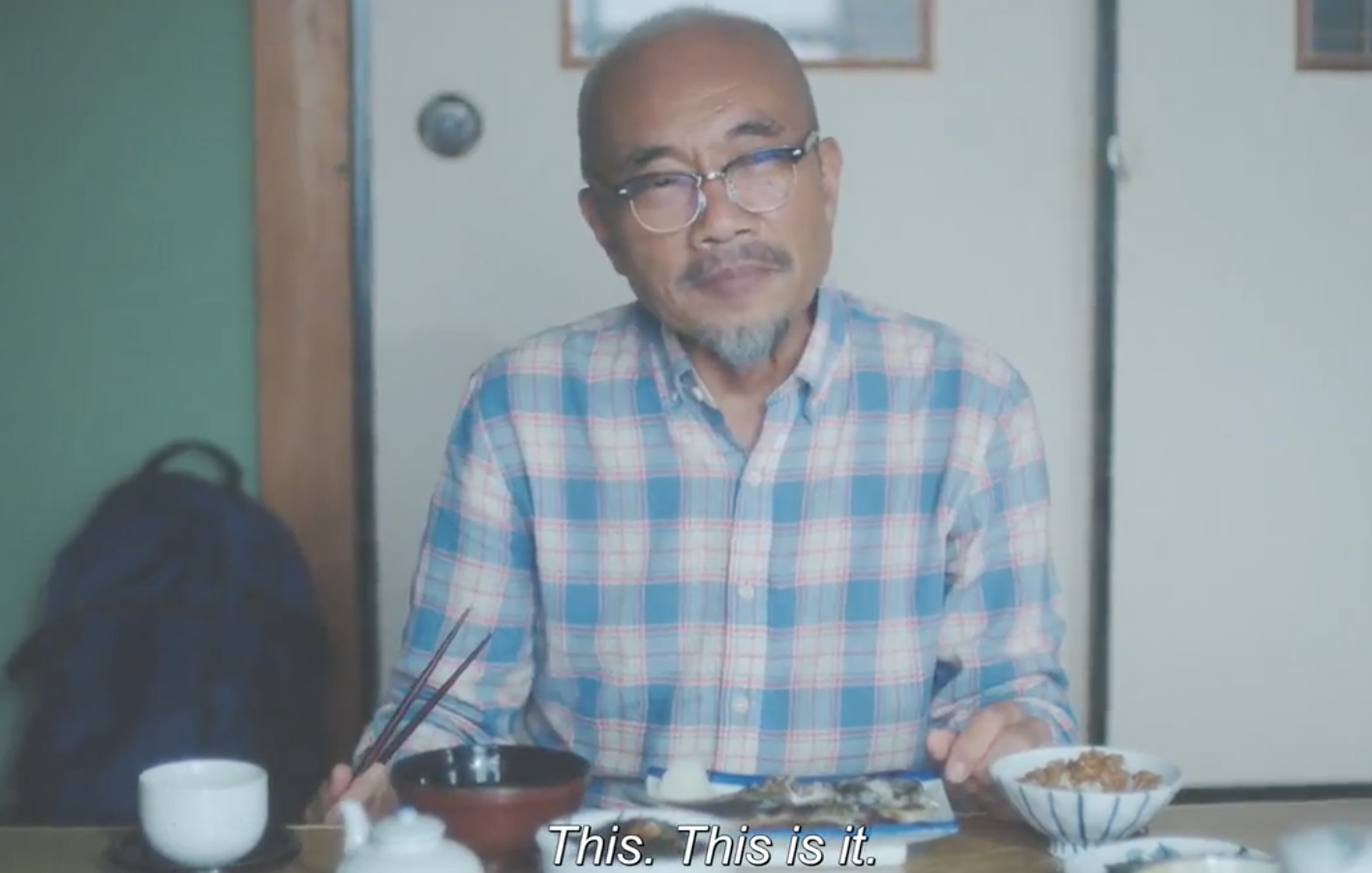

“This.

This is it.”

Takeshi closes his eyes as he chews the dried mackerel.

“It tastes like the sea.

The taste of the sea,

The taste of minerals that raised life.

It tastes like the sun.

The taste of the sun,

That makes dried fish good.

And…

It tastes like fish.

The taste of life that swims across the seas.”

What shocked me about the character of Takeshi was not his love of the food, but his love of eating it. British culture is peculiar, it has banished sensory enjoyment into the realms of the taboo. This results in a British tendency to not be an active participant in one’s own experiences. Experiences that are crystallised into memories before they can even be lived. A story already told. Nobody wants to be a spectator of their own life - I certainly don’t. So, in this kaleidoscope, appreciating things for what they really are and expressing how they really make us feel is a liberating act. But how do we go beyond that?

Takeshi is able to enjoy food because he has escaped wage labour, acquiring free time and a pension. We witness him passing through the remaining days of his life with near-total freedom. It is this freedom that provides the opportunity for profound experiences of joy. This is something that is unobtainable for many of us - the end of precarity. Life is a transient affair and should be lived to its fullest extent. However, to do this we must navigate through the systemic issues preventing us from getting there, issues that we have already identified, and forge a path forward.

The impositions placed upon our lives by the unliving commodity are done in the name of a system that is continually pulling us into the future. Modern capitalism relies on economic growth to draw investment and thereby maintain a flow of capital. This drives an obsession to blindly quantify and measure everything in order to model what may be at the cost of what is - an inverted force of history. On an individual level, capitalism is completely dominant and ever-present making it impossible to completely reject but it can be resisted.

The first challenge is seizing our immediate reality for ourselves without resorting to commercialised mindfulness or meaningless new-age slogans of positive affirmation. Live, laugh, love is not a revolutionary blueprint. In fact, we seek the mirror-image of mindfulness, which teaches us to centre the body by acknowledging sensations, thoughts, and feelings without engaging with them. We seek to centre sensation through our experience of it. And with that we have the realisation that we are searching for beauty.

What is this beauty? Food is a product of culture and of consciousness. It is a creative venture and is therefore art with its own aesthetic. Taste is how this aesthetic is experienced and that is where the beauty lies. Unfortunately, this aesthetic is entirely insular as taste is inherently unable to convey anything beyond its own interior world. This is why the sublime cannot be experienced through taste, and why its capacity for beauty is restricted in comparison to the other senses. The commodification of food has driven a complete retreat of both culture and consciousness from its production. Thus it has become an object of utility where pleasure is a function. We can conclude that if we restore beauty to food then we can drive back against the commodity that haunts it and the hologram that haunts us.

Religion gives us an idea as to how we can create beauty; a sensory experience can be enhanced through the choreography of a ritual. Take the simple act of lighting a candle in a church; the architecture, the fire, the symbols, and the physical act. There is a language here that imbues the ritual with a certain energy that makes the act feel powerful. The composition of an experience with an ensemble of other auxiliary experiences is key. In particular, ceremony and communion, outside the framework of religion, provides us with a means to exorcise the hologram: The communion of having your lunch outside in nature or eating with friends. Cooking is itself a ceremony wherein raw ingredients are transmuted into a meal. We enhance our experiences through these everyday ceremonies and reconstitute food from its fragmentation by abstract values. This is the sustenance of which we are starved.

Unfortunately, I am unable to provide anything more than a handful of suggestions at this point and that’s vastly more than I expected this article to provide. This began as, and continues to be, an exercise in understanding the things that make up the fabric of my life. It is natural then that I should pursue the paths along which my thoughts here have pointed me. We cannot think our way out of the maze we find ourselves in. We must act, uncovering the dead ends and discovering where the escape route lies. Really living. One thing I did know before I began this article was that it would become a series; there are many topics that we have touched upon which deserve their time in the light but this piece has reached a natural precipice that needs to be jumped off.

“When I was working,

I took the same route to work every day and never thought anything of it.

But now I see the value in taking a detour.

Takeshi Kasumi…

Sixty years old.

Many more destinations await me.”

References

[1] J. Chikazoe, D. H. Lee, et. al., Distinct representations of basic taste qualities in human gustatory cortex, Nat. Comms 10, 1048 (2019).

[2] K. C. Berridge & M.L. Kringelbach, Pleasure systems in the brain, Neuron 86, 646–664 (2015).

[3] Council directive on nutrition labelling for foodstuffs (90/496/EEC) (1990).

[4] J. Baker, Things No One Will Tell Fat Girls (2015).

[5] J. Baudrillard, Simulacra and Simulation p.105 (1981).

[6] G. Debord, Society of the Spectacle p.19 (1967).

[7] British government announcement (12/5/21).

[8] The Truth About Diets with Dr Giles Yeo (Video lecture).

[9] G. Yeo, Calories Don’t Count (2020).