I. Preamble

I’d driven to a nearby village with my friend Jake, who had come to visit. We passed a churchyard. There, above the low stone walls, stood a granite obelisk and fixed upon its surface was a large metal plaque adorned with the names of the war dead. These monuments are so ubiquitous that it feels absurd explaining what they are. They stand like stone antennae broadcasting a quiet signal that we’re all picking up.

Our small film club (composed of myself, Jake, and Alex) had recently veered into the territory of faith. We wanted to figure out where it came from, how it fits into modern times, and what the future holds for it. This naturally triggered a transformation in my conception of the Church. The war memorial now caught my attention in new ways. Aspects of it had previously been invisible. Camouflaged. Reflexively jotted down in my mind as something quintessentially British. Blended in with the environment and then intellectually abandoned. This had been true from every moment of my life up until this one. Now the silhouette of a new shape hung beneath the surface of the water. Looming is the word. Looming from below.

The verdant church grounds were a welcome rupture amidst the concrete so we crossed the threshold, passed through the lychgate and walked towards the structure. I attempted to identify what had called me there. I wanted to decode the signal being broadcasted. I looked first at the plaque. This was the war dead of the First World War. Forty names. Each belonging to a member of the local community; this small village. I thought about how common these monuments were. Every community had been touched by this catastrophe. Every tragic death had been forged into metal, fixed onto stone, and then locked onto the community’s heart. Lest we forget… Forget what?

“Only take heed to thyself,

And keep thy soul diligently,

Lest thou forget the things which thine eyes have seen,

And lest they depart from thy heart all the days of thy life:

But teach them thy sons,

and thy son’s sons…”

– Deuteronomy 4:9

To my left stood another granite slab and more names. All lost to the Second World War. I looked for other monuments to other wars. There were none. Why? To my mind the short answer was that both conflicts were existential threats to the modern British nation state unlike any witnessed before or since. The shorter answer was that an unthinkable number of people had died. I began thinking about the colossal trauma that the British public of the time must have sustained from those two successive wars. A vast wound etched into the collective psychosphere and kept open by tradition. Maybe I was being too dramatic. Jake and I chatted for a while about these things, reaching no conclusive answers but travelling some of the distance. This is an attempt to grasp those questions which are floating in the still air of that churchyard, miles from here, and complete their arc toward some kind of resolution.

II. Cocoon

What are these war memorials? We know their locations and geometries, but the certainty that these physical characteristics present us with is a lie. As the world changes so does the memorial. There is a process of continual transformation and renewal. A metamorphosis of meaning. As this metamorphosis occurs, in the depths of the dead realities of dead times, we catch the shifting silhouette of the memorial within the cocoon of history. Finally, it bursts forth into the immediate gaze of present day’s witnesses: You and I. Under this framing we see the historian as a tragic figure who is forever attempting to persuade the past’s shadow to shake their hand and speak its name. But there are no words: We cannot surgically extract relics from history and fully understand them because their meanings belong to the minds of the past. This truth cannot be ignored, to do so would be worse than an error. It would result in a fantasy of the past in which all things are deceptively degraded into a matter of simple interpretation. An interpretation where history is taken at face value from the standpoint of the present, as if all days since the dawn of eternity were rolled into yesterday. The artificial intimacy created by this collapsed length of time tricks us into modernizing the artifacts of the past that are thrown before our feet. My own conception of the memorial and the churchyard in which it stands is a modern one coloured by my own experiences within my own age. All of us are lost in interpreting the past lives of the things we see.

We are in good company, Nietzsche came to a similar conclusion [1]:

“The origin of the existence of a thing and its final utility, its practical application and incorporation in a system of ends, are totally opposed to each other - everything, anything, which exists and which prevails anywhere, will always be put to new purposes by a force superior to itself, will be commandeered afresh, will be turned and transformed to new uses; all “happening” in the organic world consists of overpowering and dominating, and again all overpowering and domination is a new interpretation and adjustment, which must necessarily obscure or absolutely extinguish the subsisting “meaning” and “end.”

The most perfect comprehension of the utility of any physiological organ (or also of a legal institution, social custom, political habit, form in art or in religious worship) does not for a minute imply any simultaneous comprehension of its origin: this may seem uncomfortable and unpalatable to the older men,—for it has been the immemorial belief that understanding the final cause or the utility of a thing, a form, an institution, means also understanding the reason for its origin: to give an example of this logic, the eye was made to see, the hand was made to grasp.

So even punishment was conceived as invented with a view to punishing. But all ends and all utilities are only signs that a Will to Power has mastered a less powerful force, has impressed thereon out of its own self the meaning of a function; and the whole history of a “Thing,” an organ, a custom, can on the same principle be regarded as a continuous “sign-chain” of perpetually new interpretations and adjustments, whose causes, so far from needing to have even a mutual connection, sometimes follow and alternate with each other absolutely haphazard. Similarly, the evolution of a “thing,” of a custom, is anything but its progressus to an end, still less a logical and direct progressus attained with the minimum expenditure of energy and cost: it is rather the succession of processes of subjugation, more or less profound, more or less mutually independent, which operate on the thing itself; it is, further, the resistance which in each case invariably displayed this subjugation, the Protean wriggles by way of defence and reaction, and, further, the results of successful counter-efforts.

The form is fluid, but the meaning is even more so.”

The conception of history that results from a Nietzschean approach is anti-interpretative: It is not a puzzle to be disassembled like a finished jigsaw. This is an opposing description of history to the reductive one - it pertains to an irreducible history that is near-infinite, largely unknowable, and contained within the collective experience of all humanity. To accept the anti-interpretative conception of history is to accept that we are lost amidst time. We acknowledge that there was never a clear path from what was to what is. So, if we agree with Nietzsche but wish to glean something(!) from those meanings embedded in the past, what do we do?

The reductive and irreducible conceptions of history are analogous to Markovian and non-Markovian approaches to dynamical systems found in physics. For Markovian systems, causality is reduced to a simple chain of events (1, 2, 3, 4, …) leading up to the present. Non-Markovian systems are closer to those described by Nietzsche; systems which possess a kind of memory (1, 1-2, 1-2-3, 1-2-3-4, …) such that information of prior events is contained within the current one. Non-Markovian dynamics arise when a system bleeds into with its environment, as an object mixes with its situation the two become inseparable. However, in certain circumstances non-Markovian systems can be approximated without discarding large amounts of information. This is done by isolating and focusing upon significant relationships between a system and its environment. Therefore, we accept Nietzsche’s description of the wreck of history but respond pragmatically: We shall pursue our original aim by following the war memorial on its course along history through its relationship with its situation at the time. I shall do this with what is available to me: Records from the time supplemented by academic research on the subject.

As we tiptoe towards the water’s edge, about to plunge into the depths, we condense our inquiry into two questions and hold them close:

- What functions did war memorials serve?

- What is that function now?

III. Genesis

A war memorial in and of itself isn’t unusual, but memorials to the First World War, the Great War, are notable in their prevalence across the scenery of Britain. The political foreground to the large-scale memorialisation of public spaces in the UK during and after the Great War is provided by what occured in the years immediately following the Second Boer War…

This war was a grotesque mess: Between 1899 and 1902 the British sent over 400,000 men to conquer two independent regions in the south-eastern corner of the African continent (now South Africa) held by the descendants of European settlers. Britain invested £2 million into the war (a naive extrapolation with inflation brings that value to £25 billion as of 2021). With all these resources they enacted a scorched earth policy. Thousands of people, Boers and native Africans, women and children, were forced into concentration camps. Nearly 50,000 people that we know of died.

…Peter Donaldson identifies the mass memorialisation of this war as the template which would later be followed just over a decade later following the Great War [2]. Public schools were the primary vector of memorialisation, 81 schools built memorials to commemorate alumni who died in that conflict. The funding and organisation of these memorials came from alumni bodies; the “old boy’s associations”. Edward Spiers found that 62% of army officers who served in the conflict against the Boers came from public school backgrounds, 41% of those from just ten schools, and 11% from Eton College alone. These alumni networks generously funded the erection of monuments and memorial halls in the grounds of their respective public schools.

Donaldson quotes the editor of Eton’s school magazine who said of the memorial’s purpose:

‘It would be a noble and seemly monument to our bravest and best; and though it might, incidentally, be used for practical purposes, yet its raison d’etre should be to be connected with happy and festal associations; a place where on high days the masses of the great dead should look down, well-pleased, upon the happy joys and activities of the living.’

Public schools rely on constructed traditions and identities in order to ensure that alumni are bound up with their respective institutions. They are thereby encouraged to provide “their” schools with capital (economic, social and cultural). It is upon this that their positions within the hegemony rely. The memorial is a supreme component of that, providing a spiritual link between all who attend and have attended the school. This is an important point that we shall return to: 19th Century Britain was a Land of The Faithful in that the spirit of protestantism still burnt brightly through the Anglican Church. Spiritual matters were serious and likely provided a genuine compulsion to support memorialisation for that reason alone.

Donaldson goes on to say:

‘But it was in the actions of the fallen, rather than the affections of the living, that officiating dignitaries attempted to validate institutional values. Old boys who had sacrificed their lives in South Africa were, rather like pupils who had gained regional or national sporting honors, frequently spoken of as if they had been acting on behalf of their former schools.’

Sacrifice. An important word here. Sacrifice is alluded to for two reasons: Firstly, it articulates death as something meaningful, an act of sacrifice is done in order to achieve something else - it is transactional. The reason for the sacrifice is a matter of interpretation, which can then be utilised by propagandists to claim who and what the dead died for. Claiming that it was the war dead who sacrificed their own lives moves focus away from the material circumstances of and reasons for their deaths. Secondly, sacrifice allows the war dead to mimic the story of Christ. The story of their own sacrifice then becomes sanctified and therefore the incontrovertible truth of a “Christian society”. In this way, the soldiers sacrificed themselves for us rather than the alternative; that they were sacrificed. The evocation of Christ transforms any objection to the Myth of Sacrifice into heresy.

We see in this era of memorials a grotesque valorising of war by the aristocracy and the construction of a false myth. These memorials were monuments of pride. Donaldson concludes that they were intended as sites of mobilisation not of mourning. This is the background of memorialisation as the wheel of the 20th century began to spin. For the British people those early days marked an age of naivety. A naivety that would facilitate the horrors to come and give birth to a cynicism that has since come to define many of our world-views. The tragedy, inconceivable, awaiting the people of this time would carve a vast groove into their collective consciousness. By the end, as Edward Blunden would write;

‘both sides had seen, in a sad scrawl of broken earth and murdered men, the answer to the question. No road. No thoroughfare. Neither race had won, nor could win, the War. The War had won, and would go on winning.’

This is the beginning of modern Britain. A tragedy driven by European aristocrats without vision who traded the loyalty of millions for massacres and a hundred miles of mud.

IV. The Great War Begins

From this point onwards, to lessen the impact of modernisation upon my interpretation of history, I shall be using direct extracts transcribed from newspapers at the time of the Great War. Their purpose isn’t simply to support my discussion - for the reader they provide a feeling of the times. The idea being that the extracts placed within the text here are for you to interpret too, they are able to speak more truthfully than I as they are natives of the era we are visiting. Although such extracts do not give the whole picture (something we already know is impossible to conjure) they are supplemented with other works, such as Alex King’s thesis-turned-book Memorials of the Great War in Britain, to deepen our insight. In that work King provides a substantial overview of the creation of the war memorials, from logistics to ceremony, and identifies the main actors in these processes. Furthermore, Paul Fussell’s The Great War and Modern Memory and Jay Winter’s Sites of Memory Sites of Mourning are useful tools that have informed my personal interpretation of relics half-submerged in history.

Although the first two years of the Great War were particularly deadly for British troops, minds were still focused on winning the war rather than articulating what should persist beyond it. Germany mobilised forces which were well supplied, organised, and more than ready for Britain’s entrance into the European theatre. The first year of fighting was particularly brutal. Germany’s approach to the war relied on the Schlieffen Plan which proposed that a sudden and aggressive push into the Western Front would result in a decisive victory, allowing their forces to turn their attention towards Russia in the east. For reasons we shall later discuss, the Allied Forces managed to match those of Germany in the west and the mode of conflict stagnated into nervous skirmishes from trenches dug into the earth.

As the war sputtered into existence Britain was still unveiling war memorials to those who had fallen in the Napoleonic and Boer wars. We saw in the previous section that these ceremonies were mostly organised by and for members of particular communities and institutions, mostly schools or regiments. However, two important processes had started that opened this up to a wider community: The first was a colossal propaganda campaign to recruit soldiers into the armed forces. The second was an incoherent project taken on by communities to provide spiritual and material support to the victims of war.

Newcastle Journal

17th August 1914

PRAYER AND THE WAR

THE VICAR’S SUGGESTION TO NEWCASTLE CITIZENS

Sir,

Bishop Taylor Smith, Chaplain-General to the Forces, has made a request that at noon each day every one should offer a silent prayer for our sailors and soldiers; the Bishop of Salisbury has suggested that as a reminder of this, a few strokes of the church bell might be given. In accordance with that request and that suggestion, I have arranged that each week day, immediately after the hour of noon has struck, a few strokes will be sounded on one of the large bells of St. Nicholas' Cathedral; and I venture to hope that within its wide range of sound, many places of business, in many homes, and in the streets, prayers will thus be offered.

It may interest some to know that this is really a revival of the ancient custom of the “Peace Bell,” which was rung in England from the 14th century onwards, and developed later into the “Angelus,” the Memorial the Incarnation of the Prince of Peace.

May I say further that every Wednesday and Friday the Litany, with special suffrages, will be said in the Cathedral at 12.30 p.m., to which business men are particularly invited. At Holy Communion daily at 7.30 a.m., and at evensong at 5 p.m., special intercessions are also used. I trust that there may be many willing to join us in intercession at the old church of St. Nicholas during this anxious and critical time.

EDWARD JOHN GOUGH,

Vicar of Newcastle.

P.S. In a day or two I hope to issue a short form of prayer on a card that can be carried in the waistcoat pocket for use when the bell is heard; can be had at the Cathedral on application to the clergy or the verger.

The Scotsman

31st August 1914

SUGGESTED WAR MEMORIAL

SCHEME OF HOUSING FOR WIDOWS AND ORPHANS

Mr Robert Thomson, a Glasgow architect, writes to the Press suggesting that the noblest monument which could be raised to the memory of those who may fall fighting for the safety of the nation would be such a scheme of housing as would provide homes for their widows and orphans in every district from which they came. The writer claims that the grant of £4,000,000 made by Parliament for providing work and houses is capable of providing housing for 280,000 souls in a new type of dwelling possessed of many important advantages not hitherto available.

Western Gazette

25th September 1914

Devon War Memorial

The Vicar Braunton, Devon, announces that at the close of the war he intends to place a handsome brass tablet in the Parish Church bearing the names of every man from the parish who served with the Colours.

West Sussex Gazette

1st October 1914

OUR COUNTIES AND WAR

GODALMING

The military authorities are building huts to accommodate a division of infantry and a large force of artillery on the common near Milford. This will mean an influx into the district of over 20,000 men. They are recruits to Kitchener’s Army.

A depot has been established at the Godalming Borough Hall for the reception of blankets for the troops. Sir Richard Garton, of Lythe Hill, Haslemere, has given an order to Messrs. Gammon, of Haslemere, for the following articles to be sent to the Mayor of Godalming: 150 pairs of blankets, 36 cardigans, 36 sweaters, 24 vests, and 24 pairs of pants. Nearly 1,000 blankets and other articles have been sent from Godalming altogether.

MEMORIAL SERVICE

The war is being brought closely home to all. On Friday at the Godalming Parish Church a memorial service was held for no more than three local officers who had laid down their lives for their country and King. They were in the words of the hymn paper, as follows:

In Memoriam:

Ian Graham Hogg, D.S.O, Lieut.-Colonel, 4th Hussars;

Leonard Francis Slater, Captain, Royal-Sussex Regiment;

Reginald George Worthington, Lieutenant, Oxfordshire and Buckinghamshire Light Infantry.

Killed in Action. September, 1914.

“Be thou faithful unto death and I will give thee a crown of life.”

Lieut.-Colonel Hogg was the son of Mrs. Quintin Hogg, of Busbridge Rectory, Godalming;

Capt. Slater was the son of the Rev. F. and Mrs. Slater, of Sherards, Godalming;

and Lieutenant Worthington was the son of Mrs. Worthington, of Loxwood, Godalming.

There was a large congregation in the Church, and whilst it was assembling, the organist (Mr. A. A. Mackintosh), played Schubert’s Solemn March. There were hymns and prayers - the clergy being Rev. G. C. Fanshawe (vicar), and the Rev. G. C. D’Arcy - and the service concluded with the playing of the Dead March in “Saul” and the singing of the National Anthem. The relatives of the deceased officers present were: Mrs. Quintin Hogg (mother of Lieut.-Col. Hogg), Mr. Malcolm Hogg, Sir Herbert and Lady Jekyll, and Miss Gertrude Jekyll; the Rev. F. and Mrs. Slater (parents of Capt. Slater), and Mrs Leonard Slater (widow); Mrs. Worthington (mother of Lieut. Worthington), Mr. Chas. Worthington (brother), Miss Mary Worthington (sister), and Miss Aitchison (aunt). The congregation also included the Mayor (Mr. H. Colpus), and other prominent townspeople.

Newcastle Journal

20th November 1914

A Children’s Parade

“Kitchener’s miniature future soldiers,” under the command of Jean Miller, aged three years, will parade to-morrow (weather permitting), starting from the Geographical Institute at 1.30pm. The route will be St. Mary’s Place to the War Memorial thence via Northumberland Street, Pilgrim Street, Market Street, Grey Street, Collingwood Street, Neville Street, Westgate Road, Clayton Street, Percy Street, Haymarket, to the Geographical Institute. A collection will be taken in aid of the Belgian Relief Fund.

Falkirk Herald

19th December 1914

IS YOUR NAME ON A ROLL OF HONOUR?

If your name goes down on your firm’s Roll of Honour, it also goes on that mighty Scroll which records the names of all who have rallied round the Flag.

There is room for your name on the Roll of Honour.

Ask your employer to keep your position open for you. Tell him that you are going to the help of the Empire. Every patriotic employer is assisting his men to enlist, he’ll do the right thing by you.

Tell him NOW.

Your King and Country want you TO-DAY.

At any Post Office you can obtain the address of the nearest Recruiting Officer.

GOD SAVE THE KING.

I have picked these pieces because of the tragedy they foreshadow. Death looms but it is treated as a sombre yet glorious thing done for the monarch and the nation. This is partly thanks to Lord Kitchener’s recruitment campaign. His propaganda was so impressive that, over a century later, the recruitment posters remain in popular culture. He was Chief of Staff during the Second Boer War and an imperial creature that seemingly conceived of war as a game. One should look upon the jubilant parades led to recruit “Kitchener’s New Army” with great cynicism - in order to bolster numbers to match continental powers Lord Kitchener devised a campaign to encourage working class men with no military training to sign up and fight. Another notable feature is the memorial service. These church services would continue throughout the war, much of the ritual of Rememberance would be extracted from them. However, they do not serve the same social and historic function as the monuments, the war memorials.

War memorials speak to us of legacy. Through them the nation proposes that history is the story of the exceptional few upon whom the many depend. Such a story necessitates that those who gaze upon it are convinced of the inadequacy of their own legacy. Kitchener’s propaganda exploits the absence of working class names in the national canon. He is offering the Forgotten Ones a chance to break out from the shadows of anonymity and stand amidst history as individuals. The medium for this glory is the Roll of Honour. The Roll is a list of those fighting in the war compiled by the communities and institutions that they belonged to. It is a doorway etched into the grey bedrock of the nation, across its threshold lies the world of the symbolic. The placement of a name upon the Roll of Honour is a binding ritual where the individual, reduced to an icon, is woven into Britain’s myth. But we mustn’t get ahead of ourselves…

Let us stop and take stock. We need to pluck a thread that will lead us to the modern war memorial. This can’t be done by assuming that the first celtic cross dedicated to fighting men unveiled during the war is what we’re interested in. Alex King identifies a number of such memorials that were awarded to towns in 1915 for having a very high proportion of enlisted men. These structures were tools of recruitment, there is no real sentiment behind their creation and therefore not much value to our inquiry. Memorials, like all human works, are machines with seen and unseen components whirring away; bodies and embodiments. The components are tangled together by circumstance and design. The war memorial of the Great War is no different. In this light, we are interested in a certain formation of war memorial; a formation that placed a previously anonymous section of society within the national story of the war by centring Rolls of Honour amongst sculptural forms that are aesthetically consistent in their sombre portrayal of sacrifice, something we shall revisit. Where do these structures come from?

V. Together

It’s curious how time works; our position in the future means we watch the war tumble further into the past like a train that has already passed us by. From that comfortable position trench warfare appears as an alien moment that lasted the duration of the war and then simply evaporated. Despite its transience the unique, surreal and grim reality of life in the trenches made a deep impression upon those who suffered through it. Jay Winter eloquently captures how this experience of the European front was translated into sentiment:

“The otherworldly landscape, the bizarre mixture of putrefaction and ammunition, the presence of the dead among the living, literally holding up the trench walls from Ypres to Verdun, suggested that the demonic and satanic realms were indeed here on earth. Once this language had a foothold in everyday parlance, it became easy for ordinary men to imagine that hell was not some other place, some exotic torture chamber under the trap doors leading to the nightmare worlds of Hieronymus Bosch or Roger van der Weyden. To all too many Englishmen and women, Hell was indeed just across the Channel.”

We must remember that the soldiers spent months below level ground. During that time there would have been very little evidence as to who or what the enemy was. Without those fleeting moments, a helmet above a trenchline or a distant cry in a foreign tongue, the enemy may have seemed like phantoms. We know and understand that these conditions were fraught with paranoia, something that men would bring back home and share with their families. In the summer of 1916, members of the Anglican clergy of Hackney who had noticed these anxieties decided to act. It was the rector of St John of Jerusalem Church, Rev. Basil Staunton Batty, who initiated a movement that would develop the structures and rituals that are an intrinsic part of what we understand the war memorial to be today.

Weekly Dispatch (London)

4th June 1916

SIDE-STREET WAR SHRINES

By Russell Stannard

On any fine Sunday evening just now you may see a little procession making its way to one or other of the poorer parts of the Borough of Hackney. At its head is a trench-stained warrior bearing aloft a cross of bronze, and behind him follow little boys in uniforms of the Church Lads’ Brigade carrying the flags of the Allies, then choirboys and clergymen in their surplices, and lastly, some elderly civilians. You would do well to follow them as I did last Sunday because they are going on a wonderful pilgrimage.

They are going to pray at one of the shrines of the side streets of London. It was just after eight o’clock by the summer time and the sky was still bright with the spring sun when the procession turned into a little thoroughfare called Eaton-place. Eaton-place is not a slum according to present-day standards; it may be thought so a generation or two hence, but on this Sunday it looked a glad place to live in. There were flags at the windows and streamers of them hanging across the street. There were women with careworn, but cheerful faces sitting outside the doorways, and healthy children, with clean faces and white pinafores. There were no men there.

As the procession went down the street some of the women and children joined it and went with it to a spot where others were waiting. Here they all halted. On an ugly brick wall was the shrine of Eaton-place. A card with columns of names written upon it hung in a wood frame from a nail. The names were those of the men of Eaton-place who have gone away to fight - 69 of them from 62 houses. Four of them are dead.

On either side of this frame were metal vases filled with fresh flowers. There are always flowers in them. Above them the flags of the Allies and another frame with a card bearing “A prayer for the loved ones away.” Eaton-place opened a subscription list and bought these flags and flowers themselves.

A hymn which attracted all the mothers and the babies and the children who were still indoors opened the proceedings. The children clustered round the Rector of South Hackney; the Rev. B. S. Batty, who stood on a soapbox. He is one of those big clean-shaven, open-faced clergymen whom the London poor instinctively trust. He has been to the front, and come back with his heart full of love of the men he left behind, and of compassion for their relatives. After the hymn he took down the Roll of Honour.

“Here are the names of those from this street who are serving their country. Let us pray for them.” He read them out. Then he read one of the simple prayers that have been issued by the Bishop of London and after that everybody repeated the Lord’s Prayer.

THE VICAR’S ANECDOTE

“You know,” said the rector, smiling, “we have come down here this evening to show you how greatly we appreciate the sacrifices that so many of you have made on behalf of your King and country. We know of your great anxiety about those who have gone out to the front and we want to show you how to put them into God’s care.”

The rector paused for a moment then tried something in a lighter vein. “I remember as a curate officiating at my first wedding and giving a very long address to the couple. In the middle of it they began to look very anxious, and somebody tugged at my surplice and a voice whispered to me: ‘Don’t be too long because they’ve hired the cab outside by the hour.’”

The mothers who had been looking sad now laughed and the babies enjoyed the joke. “Why is it I believe that these prayers of ours are going to affect the course of the war?” asked the rector, who began to tell the parable of the shells.

“If it had simply been a matter of men and munitions this war would have been over fifteen months ago and we should have been beaten. In September 1914 our enemies had all the highly trained men they wanted and they attacked us when we had practically no ammunition. I was at the front at the time. For every 100 shells fired by the enemy we could only send back one. I say without a moment’s hesitation that men and munitions, important as they are, are not going to decide this war in the end. I believe God’s decision is going to settle it, and that the nation that calls upon God with prayers and believes that He has the final voice will have the victory.”

FLOWERS NEVER TOUCHED

Eaton-place were greatly impressed by this and earnestly sang a prayer:

“Holy Father in Thy mercy

Hear our prayer.

Keep our loved ones now far abroad,

In Thy care.”

They sang it over softly and liked it so much that they sang it twice again. There were no tears. The rector told the mothers to “teach it to the kids” to sing before going to bed.

That was all there was in the service. It lasted barely a quarter of an hour, but Eaton-place seemed somehow very much the better for it. The women looked as if a load of care had been lifted off them.

“I have had several letters from the men at the front about this.” said the rector to me. “They seem to like the idea very much. They have had picture postcards sent [to] them of the roll of honour with the flags and the flowers. One man wrote: ‘It’s like the wayside shrines you see in France.’”

“We have for others in Palace-road, a few streets from here, where 106 men have gone from 70 houses, and in Frampton Park-road, where 86 men have gone from 80 houses. We are going to do as many streets as we can and hold a service in one of them every Sunday afternoon or evening. The idea seems to be good and I have hopes that it will be taken up in other parishes because I believe it’s a consolation to these brave people. Most of the men went very early in the war and the women and children have been alone ever since.”

Mr Batty told me that there is always a soldier on leave about anxious to head the procession with the crucifix. He has never been able to keep a flower in the rectory garden, but the flowers in those vases are never touched until they are replaced with fresh ones.

“It’s very nice of the parson to do this,” said one woman who has six sons at the front. “It comforts one in these days to see something that kind of cheers you up when you get no news. There’s a woman over there what’s had her son missing in the Dardanelles since last August. Hasn’t heard a word from him. His brother went out there to find him and got wounded [when] he landed. Their names are up there on that roll. There’s a woman down at the end of the street whose husband has been killed and left her with six little children - rather sad, ain’t it?”

I like to think of these street shrines appearing, as I think they will, in the side streets of every borough in London. They are symbols of a nation’s sacrifice which the youngest children running about those same streets can understand. They mean a great deal to the people whose fathers, husbands, and sons have gone. Life in these side streets of London is still. The ebb and flow of the main thoroughfares scarcely penetrates. More than ever now that the men have gone is the life self-centered. The mothers and the children all day have nothing else to think about but the peril of their loved ones.

That is why the side street makes such an unlovely but noble sanctuary. And the men out there know all about it, and more than one has the picture of the shrine next his heart.

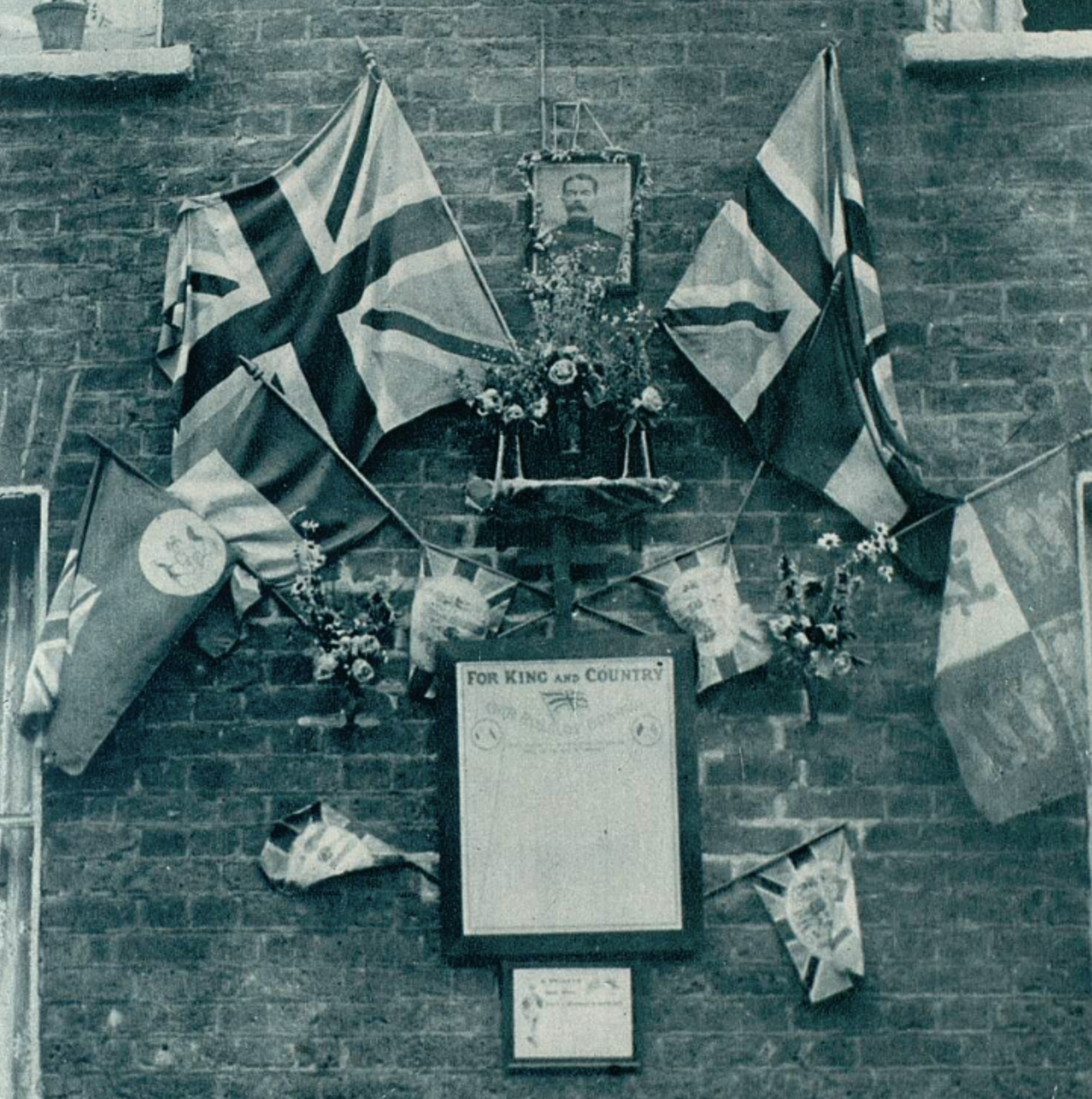

Illustrated War News

12th July 1916

A TRIBUTE TO THE BRAVE

A ROLL OF HONOUR, FLOWER-DECORATED, IN A LONDON STREET

Although a handful of war memorials were being erected in more prosperous regions of the country from as early as 1915, these street shrines provide memorialisation for those who couldn’t afford such a thing. But it’s more than that: They offer something else. They are not singularly dedicated to mourning the dead, on the contrary they are predominantly concerned with the living. This is an effort at solidarity by those at home with those in the trenches. By paying tribute to the soldiers and maintaining these shrines, friends and family could feel as though they were actively involved in the war effort in some way. The shrines provide a physical space within which, through ceremony and aesthetic, God is implored to provide those fighting with divine protection. Within the spiritual aspect is a social one: The street shrines grounded the departed in the geographies that they had left. Dead, alive, or missing, they were all brought home and they were all recognised by their community as heroes. One can imagine how deeply affirming it would’ve been for the soldiers to know that there was somebody at home thinking of them and watching over them.

The desire to support those on the frontlines in this way caught on: In Derby, vicars designed and constructed similar shrines for their parishes [3]. The shrines became a nationwide phenomenon. Their aesthetic is particularly interesting. Britain’s protestantism translated into an iconophobia, a distaste for symbols in faith, and because of this the cross was not as ubiquitous a symbol as it was in many catholic countries. This vacuum and how numerous the shrines allowed the cross to become synonymous with the war dead. As we hear the rector in Hackney say, they reminded many soldiers of the wayshrines they had seen on the continent. This raised concerns; you will find many letters in newspapers bemoaning the perceived idolatry as Catholic propaganda.

Within a year the shrines had acquired sufficient social capital that unveilings and celebrations were an opportunity for civic leaders to make an appearance. Queen Mary even visited Hackney with the sole purpose of seeing the street shrines for herself [4]. This is an important intrusion for the monarchy which sets a precedent: From here onwards, the Royal Family would persistently encourage communities to take part in the construction of shrines and the memorials that would follow. This effectively co-opted the movement. Given the presence of the King’s photograph in the composition of many street shrines it is unlikely that this was unwelcome. This is quite literally a national cult - as the country mourns so does the Royal Family. Jay Winter tells the story of the family of a soldier named Malcolm Wakeman who are struggling with bureaucracy to mourn him in a dignified way [5]. Despite the military charging him to visit his son at his deathbed Wakeman’s father later expresses his pleasure at receiving condolences in a telegram from the head of the Army; the King, and confides in him his sense of loss. Just as we see today, the Royal Family manages to establish a distance between themselves and the actions of the state which they are embedded deeply within. They are seemingly both hostage and hostage-taker.

Following the support of the Royal Family came that of the nation’s institutions. The effect was a significant expansion of the resources available for the construction of new shrines and their accompanying ceremonies. The shrine movement migrated away from the working class communities it began in and moved towards civic centres. Parallel to this, as the war would roll on, those on the frontlines would continue to die in shocking numbers. For many of the young working-class men who lost their lives their name on a street shrine would be one of the few visible signifiers that they ever existed. The war dead were a growing demographic and, unlike previous wars, their names were being broadcast directly into the heart of their communities through the street shrines. With that the character of the shrines shifts for those who visited them. Towards the end of the war we witness a culminating moment wherein the articulation of death, the nation, and faith is so similar to the modern Remembrance ceremony that we must assume it is the archetype.

Daily News

26th July 1918

AUGUST FOURTH

Services in Hyde Park: Shrine of Flowers In Memory of Dead Heroes. Arrangements have now been completed for the August 4th services which are to be held in Hyde Park. The Bishop of London, who will be accompanied by the Lord Mayor and the Mayors of Paddington and Westminster, will deliver an address from a stand near the Marble Arch at 3.15.

A shrine will be erected nearby, and contributions of flowers may be placed upon it from 2 o’clock. It is hoped that the King and Queen will be able to view the flowers during the afternoon. The Lord Mayor asks that only inexpensive floral gifts should be made, consisting of simple sprays and single flowers. The flowers will be collected by the London Volunteer Rifles - who will act as a cordon during the afternoon - and taken to the military hospitals. Offers of motorcars for this purpose will be appreciated. The suggestion is made by the Duke of Connaught and the Marquis of Lansdowne that unless the collections to be made in the churches on August 4 have already been allocated to some other purpose, the whole or part of them should be devoted to the care of our prisoners of war in enemy hands.

Daily News

5th August 1918

HYDE PARK SHRINE

Many Thousands Pay Their Tribute to Fallen

A huge crowd gathered in Hyde Park for the impressive service at the great war shrine erected there. Many thousands of people brought simple floral emblems to place upon it in memory of the fallen, and the Bishop of London, who conducted the service and delivered an appropriate address, blessed the offerings. In addition to the Bishop of London, who declared that four years ago the nation did the most righteous and Christlike thing in its history by going to the rescue of the weak against the strong, the Rev. F. C. Spurr and Dr. Sherwood Eddy addressed the gathering. Dr Eddy, one of the American Mission, said by the end of next year America would have 50 times the amount of shipping tonnage that she had on entering the war. She was late in, but she had come in with a plunge.

At the close of the service a procession was formed to the shrine, which bore the flags of the Allies and was surmounted by the Cross. The floral gifts were arranged in the shape of a cross at its base. Children brought a very large number of them, and were led to the shrine by members of the London Rifle Volunteers. One baby, three months old, was carried by a sturdy N.C.O.

Noticeable among the wreaths was one of laurels, with a large photograph of General Maude. A card bore the inscription: ‘in memory of a dear brother and the splendid men who died in Mesopotamia, from Miss Alice Maude.” Close by it was a simple wreath: “In proud and loving memory of my three dear sons, who all gave their lives for England’s sake.” Some Gurkha soldiers brought up a tribute to one of their officers, while Miss Lilian Braithwaite brought one: “To the memory of a dear husband and daddy.”

When the Bishop reached the shrine the Lord Mayor of London advanced with his two grandsons, and placed a small tribute among the others, and the Bishop of London did the same immediately afterwards.

The shrine was blessed, after which the procession was reformed, and made its way out of the Park, headed by the Salvation Army band.

Daily Mirror

5th August 1918

Globe

14th August 1918

PERMANENT SHRINE

Mr. C. P. Higham, Organising Secretary of the War Shrine Movement, stated to-day that Mr. F. J. Waring and Sir Alfred Mond are to-day meeting to consider the erection of a permanent Hyde Park memorial to those who have fallen in the war. Mr. J. R. Clynes, the Food Controller, to-day visited the Shrine and placed a bunch of pink carnations on the memorial. “My feelings in approaching this ground and looking at the cross of flowers,” he said, in a brief address, is a desire to kneel down and pray. The symbol which is erected here could only spring from our sense of the nobility of sacrifice covered by the names of the men who have died in the greatest of all causes.

“No small or separate monument could do justice to the collective heroism of the men who have fought and died together, and it is, therefore, fitting that in this great centre of the Empire a simple collection of flowers should be used to indicate the sense of national thanksgiving which is felt throughout the Kingdom for the patriotism and bravery of men of all classes who have died for the common cause.”

Mr Clynes expressed the conviction that the War Shrine Movement should be continued; it afforded an outlet for a true, deep, and emotional feeling, and a means of appreciating at its true value the greatness of the service rendered.

The Hyde Park ceremony falls upon the fifth anniversary of Great Britain’s declaration of war. In that time the object of the service shifted from the living to the dead. The war is months from being won and attentions have turned away from what must be protected and towards what has been lost. This comes across as a compulsion in the extracts. In modern times, the sentiment of indebtedness to the fallen has become a truncheon with which to enforce participation in the rituals of the national cult. Such participation is a performance to demonstrate respect for the symbolic dead whereas here, at the actual origin-point of the war ceremony, what matters is showing thanks for the perceived act of sacrifice made by the real dead, people known by those in the crowd. But we can understand that even this is artifice from those reporting on the story at the time because, beneath everything, is the immediate and personal reality for the people of the nation; they wanted to mourn.

The ceremonies served an emotional function for the majority of those who attended, I agree with Jay Winter’s interpretation that “communal commemorative art provided first and foremost a framework for and legitimation of individual family grief.” It was the desire to grieve that ignited the compulsion to gather at the shrines in the final days of the Great War and therefore justified their existence. The popularity of street shrines and their organic spread across the country is evidence of how much the lives of the soldiers meant to their communities. However, this is not true for the civic leaders present who perceived the political functions of the ceremonies; take the presence of, and the time given to, the American delegation at Hyde Park.

The meetings between Sir Alfred Mond (First Commissioner of Works) and Waring mentioned above would lead Sir Edwin Lutyens to be commissioned for designs of a permanent shrine in Hyde Park. Unfortunately, that shrine was never transformed into a stone monument but another temporary shrine designed by Lutyens would make the ascent - the Cenotaph. The transmutation into stone reflects an intention by the twin institutions, Church and State, to canonize the shrine movement - incorporating its ceremonies into tradition and cementing it into the national cult. Why? Because these institutions own the land upon which such monuments must be built, churchyards and civic centres, and they are the ones who must maintain them. That is the next part of the story for the next piece, where we witness a form of sanctified militarism emerge that leads directly into the obsessive nostalgia that dominates the minds of modern times. But let’s wrap things up here before venture there.

In this piece we have briefly explored how the British state’s conception of history has been used against those who it intentionally ignored, common people, in order to bolster its military force through propaganda. At work here is a bargain: The people are to fight for their nation and in return they shall become icons within history. These icons, their names, sat upon the Rolls of Honour which sat within the local church until the invention of the street shrine. The shrines allowed sacred space to be projected from within the church out into the community. Through ceremony, the icons became placeholders for those they named, but when the named passed away the icons were all that remained. I don’t see how it’s possible to feel anything less than sympathy for the people of this time: For those who were recruited into the Armed Forces and those who they left behind. The suffering of the former and the grief of the latter are evident and real. However, the same machine that pumped out Kitchener’s propaganda was still at work - our hegemon, the dominant culture of British nationalism. We saw its wheels turn as the street shrines became a popular phenomenon and their social function deeply institutionalised. As we will discover next time, in what was either an act of self-protection for the state or a genuine delusion of parental responsibility, the hegemon repeated what it did following the Second Boer war by integrating the story of Christ with the soldier-icon. In this way the icons became actors within a play where the hegemon took centre stage. It is the hegemon who will be the focus of the next piece and who shall reluctantly guide us back to the present day.

References

[1] F. Nietzsche, On the Genealogy of Morals (1887).

[2] Donaldson, P., The Commemoration of the South African War (1899–1902) in British Public Schools, History and Memory, 25(2), 32–65 (2013).

[3] Derbyshire Advertiser and Journal - Saturday 18 November 1916.

[4] Berks and Oxon Advertiser - Friday 18 August 1916.

[5] J. Winter, Sites of Memory, Sites of Mourning: The Great War in European Cultural History.